Europe's Energy Crunch: No Time for Complacency

By Thijs Van de Graaf

[December 2022]

Thijs Van de Graaf is Associate Professor of International Politics at Ghent University, Belgium. His research covers the intersection of energy security, climate policy and international politics. He is co-author of Global energy politics and served as the lead writer on two IRENA reports on the geopolitics of the energy transformation.

Ten months after Russia's invasion of Ukraine, winter has arrived in an energy-crunched Europe. Despite this, the mood is surprisingly optimistic. Gas prices have more than halved since the summer and the continent has filled its gas storages to comfortable levels, making shortages this winter very unlikely.

While it may seem that the tides have turned in the EU's energy war with Russia, it is way too soon to declare victory. Recent trends in prices and storage are positive signs, but they should not lull Europe into a false sense of energy security. Instead, Europe should continue to prepare for a lingering energy crisis in 2023, and beyond.

Europe’s response to the energy crisis so far has been too slow, disjointed and, in some cases, incoherent. If Europe does not get its act in order, it faces a risk of (energy) market breakdown and a backlash on efforts to decarbonize. But if it rises to the occasion, the EU can emerge stronger and more resilient from the energy shock.

Europe’s gas troubles are far from over

Gas prices: still overheated

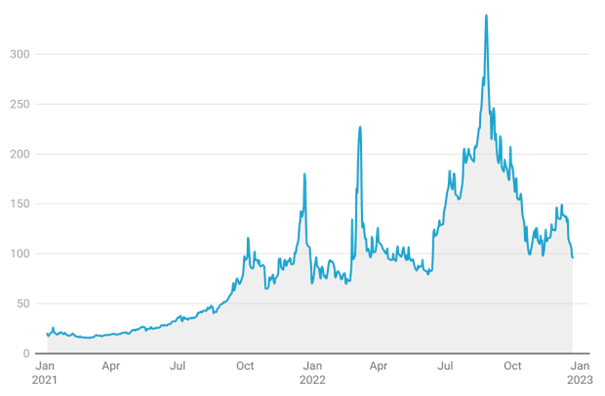

Wholesale gas prices have dropped by nearly two-thirds from their peak of almost €340/MWh in late August, despite Russia cutting most of its pipeline gas supplies to Europe (Figure 1).

The decline in gas prices is remarkable and is providing much-needed relief to Europe’s economy. Yet, wholesale gas prices are still hovering around a hefty €100/MWh—more than 5 times above the average of 2010-2019.

Figure 1. Wholesale gas prices in Europe (front-month TTF, €/MWh)[1]

Moreover, future contracts point to an enduring tightness in gas supplies. The current forward curve suggests that gas prices will average well over €110/MWh in 2023 and over €90/MWh in 2024. For comparison, Europe’s pre-2021 gas prices never exceeded €30/MWh.

Although forward curves must be treated with caution, it seems safe to say that Europe is not returning to the pre-2021 gas price levels. This crushes any hope that the gas crunch would be a short-lived event, confined to this and the previous winter.

Storage: winter buffer is not enough

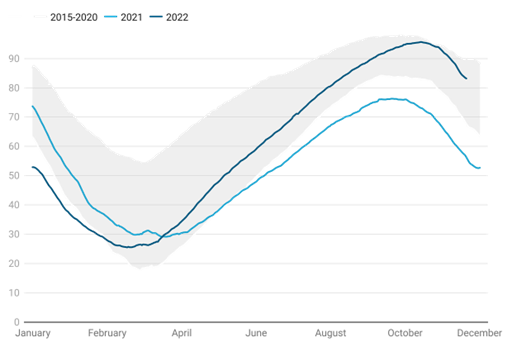

Gas demand is seasonal and underground gas storage is essential to meet winter demand. In 2021, Europe started the heating season with historically low gas storage levels (76% on November 1st).

This year, the European Council adopted a minimal storage obligation of 80% for November 1st. The EU by far exceeded its own target and hit almost 95% (Figure 2).

Figure 2. EU gas storage (% full)[2]

However, storage is not enough. Storage typically meets only 25-40% of winter demand. A steady stream of production and imports is still required.[3] In the winter of 2021-2022, Russian pipeline gas was still flowing into the EU (albeit at reduced rate). This winter, Russian gas flows have fallen to a trickle.

Europe needs to have enough gas in store at the end of the heating season. If storage levels fall below 50%, the withdrawal rate also begins to fall precipitously. This could be dangerous in the case of a late cold spell, say in March 2023.[4]

Depleting storage levels also make Europe’s task of refilling storage ahead of the 2023 winter a lot more difficult. This is important, since it will likely be the first filling season without access to Russian pipeline gas (zero gas pipeline imports from Russia in 2023 is now the IEA’s baseline scenario).[5]

Energy savings: cold comfort

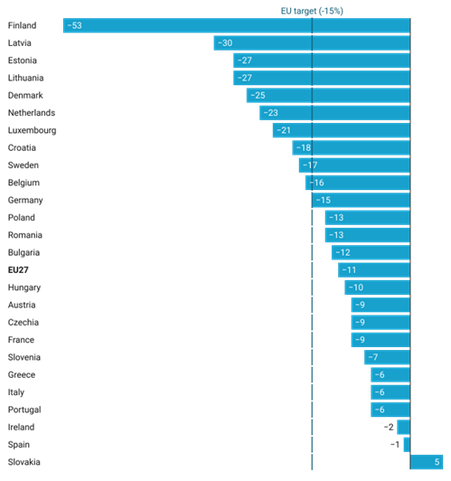

Europe’s gas demand has been significantly reduced in the face of high gas prices. Across the 27 member states, gas demand has fallen by 11% between January and November 2022, compared with average demand in those months between 2019 and 2021.

Figure 3. Gas savings in the EU (% of savings in Jan.-Nov. 2022 compared to avg. 2019-2021)[6]

However, this still falls short of the mandatory target of 15% reduction in gas consumption that the EU set for this winter. Part of the savings are sheer luck. Gas consumption has been moderated by unusually mild temperatures in the Autumn.[7] A few cold spells during the winter may put Europe’s readiness to save gas to the test.

Moreover, not all energy savings are alike. A household voluntarily turning down the thermostat is not the same as one facing a choice between heating or eating. A brewery switching from gas to oil is not the same as a fertilizer plant shutting in production for weeks or even months. Energy savings are to be encouraged as long as they don’t incur social or economic pain.

There is no evidence of deindustrialization in Europe yet. Industrial manufacturing output has gone up over the last year.[8] Yet, many industries have been shielded from high prices by long-term energy contracts, which will expire at some point. As Nikos Tsafos aptly put it: We should beware of ‘economic ruin masquerading as “energy savings”’.[9]

LNG lifeline: freedom molecules?

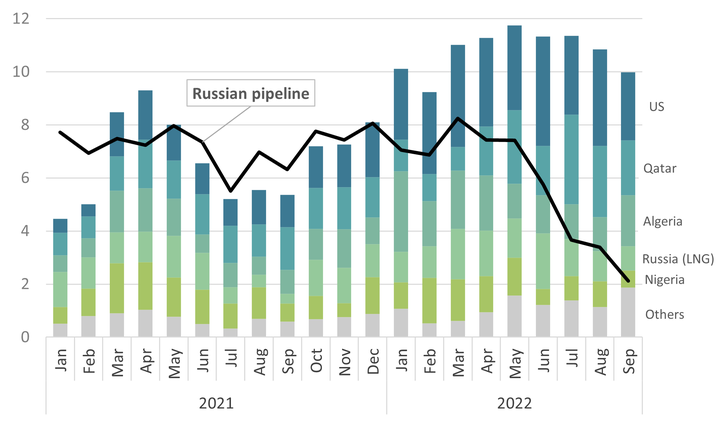

As Russia closed the gas spigots, Europe has diversified to other suppliers. If it was not for the massive influx of LNG (with the US now the top supplier), Europe would have probably needed to resort to rationing.

Figure 4. EU Import of LNG and Russian pipeline gas (bcm/month)[10]

Repeating that feat next year will be harder. Europe’s record LNG inflows in 2022 were partly enabled by lower demand from China due to covid-induced lockdowns. In 2023, China’s LNG import needs may grow by 20 billion cubic meters (bcm), effectively eating up all of the growth in global LNG export capacity, which is expected to be modest anyway.

Moreover, the reorientation of gas trade flows sometimes looks more like problem shifting than a real solution. Ironically, for instance, Europe has increased its imports of LNG from Russia in the past year.

The EU now routinely touts non-Russian gas suppliers as ‘reliable’, including Qatar (currently in the eye of a corruption storm hitting the European Parliament), Azerbaijan (which recently attacked Armenia), and Algeria (which threatened to cut gas supplies to Spain in April).

With European companies scooping up a large portion of LNG spot cargoes (and even some cargoes sold under long-term contracts to other destinations), it has partly exported its energy crisis to the rest of the world. Developing countries with less deep pockets have struggled to secure LNG imports. As a result, many have resorted to coal and some, like Bangladesh and Pakistan, even suffer from routine blackouts.

The West has not yet won the energy battle

In recent months, Ukraine has made impressive gains on the battlefield. However, in energy markets, the West has not yet emerged victorious. This is particularly apparent in Ukraine, which is facing a cold and dark winter due to Russian attacks on its energy infrastructure.

The rest of Europe may feel that they have the upper hand in the energy battle with Russia. After all, the EU has effectively banned imports of Russian coal (since August 10) and crude oil delivered by ships (since December 5) without wreaking havoc on energy markets. In fact, both coal and oil prices have declined since the embargoes took effect. And on top of that, Europe has stomached Russia’s gas cutoffs.

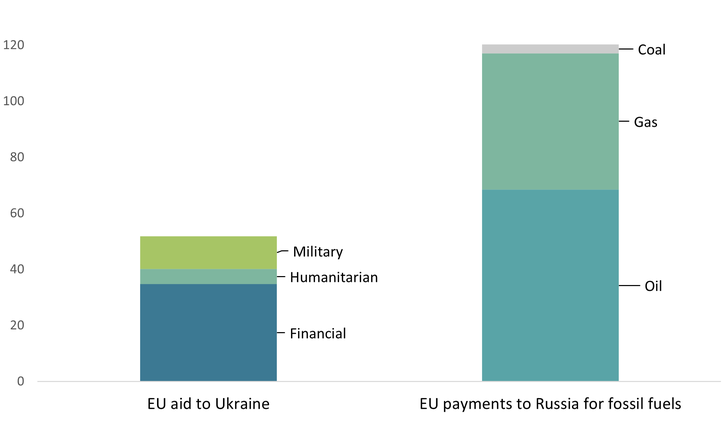

Yet, the reality is also that Russia has profited greatly from the war. Over the past few months, the EU has spent twice as much on payments for Russian fossil fuels than on aid to Ukraine (figure 5). In just the first five months after the invasion, Russian oil and gas revenues more than doubled compared with the average of previous years.[11] It is clear that the energy battle with Russia will be a long and complicated one.

Figure 5. Financial transfers from the EU to Ukraine and to Russia since the invasion (bn €)[12],[a]

Russia and Europe both stand to lose in the gas war

In the REPowerEU plan, proposed by the European Commission in May 2022, the EU aimed to reduce its imports of natural gas from Russia with two-thirds by December.[13] This target was deemed ambitious by the IEA, which had proposed to reduce those imports by just one-third.[14]

In the end, the unravelling of the decades-old gas relationship between Russia and Europe was done at a pace set by Moscow, not Brussels. Russian gas pipeline exports to the EU dropped by 80% in 2022.

Thanks to a massive surge in LNG imports (up 60% from 2021 levels)[15], Europe was able to replenish its gas inventories for the winter, but only at a very high cost—some €50 billion or 10 times the historical average.[16] This import bill will likely remain elevated for years to come. Bloomberg has calculated that surging energy costs in the fallout of Russia’s war in Ukraine have already saddled the EU with a cost of roughly $1 trillion, and the state of emergency could last for years.[17] Governments have pledged to offset roughly €700 billion with aid packages[18], but their fiscal capacity is already stretched and rising interest rates make it even harder to issue debt.

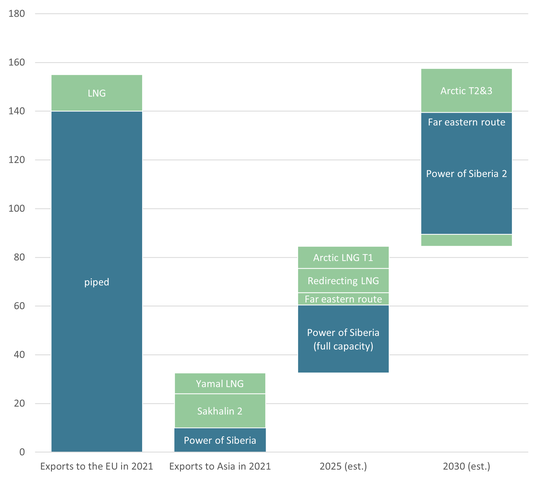

Russia, from its side, is no winner either. Moscow’s scope to pivot its gas sales to the other markets is limited by a lack of infrastructure. Russia supplied just over 30 bcm of gas to Asia in 2021, compared to 155 bcm of gas exports to the EU. In a best-case scenario for Russia, it will take at least a decade for Russia to scale up its gas exports to Asia to match the pre-war export levels to Europe (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Time needed for Russia to shift its gas exports to Asia[19],[b]

Russia can also forget about becoming a main supplier of gas to Europe again, not just because Nord Stream, the main conduit to export natural gas to Europe, was damaged in an act of sabotage, but also because its reputation as a reliable supplier is completely in tatters.[20]

Oil warfare: brace for a diesel shock

Although oil prices have fallen in the last 6 months (from over $120 to under $80 a barrel), it would be a mistake to think that Europe's energy problems are limited to gas. In fact, the strong dollar has caused the eurozone to experience an oil shock this year. Oil prices in euros have never been higher than they were in June 2022, and while they have decreased, they remain elevated by historic standards.

Moreover, beneath the surface, tectonic shifts are occurring in the oil market. In 2022, IEA member governments agreed to release almost 200 million barrels of oil—the largest stock release since the agency's founding in 1974. These releases only provide temporary relief, however, and the US government is already planning to refill its strategic storage instead of releasing more stocks. Meanwhile, ‘OPEC Plus’—a group of about two dozen oil-exporting countries led by Saudi Arabia and Russia—decided to reduce their collective output in October, further decreasing global oil supply.

Since early December, the EU's embargo on seaborne crude oil imports from Russia has gone into effect, along with a G7-agreed oil price cap. The price cap means that Western maritime insurance companies—which provide about 90% of global maritime (re)insurance services—can only cover tankers carrying Russian oil if it is priced below $60 per barrel.

The Western oil embargo is thus fiddled with loopholes. Hungary got an exemption from the crude oil embargo, which can still be supplied through the southern leg of the Druzhba pipeline. At the insistence of the US, the EU’s embargo (which originally included a full ban on insurance) was weakened by the price cap mechanism. It appears that Washington’s fear of supply shortages and price spikes was higher than its desire to reduce Putin’s oil export revenues.

Yet, the oil embargo’s full effects have yet to be seen. The real test will probably come in early February 2023 when the EU’s embargo on oil products (such as diesel) kicks in.

The EU’s energy crisis response has fallen short

While the EU rightfully places much of the blame for its current energy crisis on Moscow, there are many things it could have done better.

Sleepwalking into an energy crisis

In a way, the EU (and some of its major member states) sleepwalked into an energy crisis that was partially self-inflicted. After Russia had cut-off gas to Ukraine several times, and annexed Crimea, the EU vowed to reduce its dependence on Russian gas. In reality, the opposite happened. Business as usual prevailed, with the emphasis on ‘business’. The EU’s mantra was that a liberalized internal energy market provided the best guard against energy security threats.

However, the pendulum swung too far toward unfettered markets. The EU’s liberalization packages included ‘ownership unbundling’ for gas production and transmission, but not for storage. This allowed Gazprom to begin squeezing Europe’s gas market in the summer of 2021, when it failed to refill its storage sites in Germany, the Netherlands and Austria. The fact that there were no mandatory gas storage obligations at the EU level also reflects the dominance of the market paradigm.

On the supply side, gas markets were not liberalized. The interlocutors of European utilities were state-owned companies like Gazprom, Equinor, Sonatrach and Qatargas. The EU was effectively a “liberal actor in a realist world”.[21] The height of the blind and naïve faith in market forces of some European elites was exemplified by Germany’s insistence that Nord Stream 2 was just a “commercial” project, and by the fact that it did not build a single LNG import terminal, even as insurance.

Crisis management: too little, too late?

The EU acted too slowly in addressing the energy crisis, particularly in regards to energy savings, which is a key and no-regret measure. It wasn't until August 2022 that the EU adopted a gas savings regulation, and even then, the savings were not mandatory.[22] It took even longer to come up with an electricity demand reduction plan, which also remained non-binding.[23] The energy crisis did not start on February 24, but months earlier. Discussions on joint gas purchases, wholesale gas price caps, and other measures have dragged on for months.

The EU also responded to the crisis in a disjointed way. At the start of the crisis, it merely offered a toolbox of policy options but essentially left it to individual member states to figure out their responses. Some governments implemented measures that primarily benefited their own companies and households, using tools not available to others. Spain and Portugal capped the price of gas for power generation (an extraordinary measure justified by the Iberian Peninsula’s limited interconnection with the rest of Europe), France froze power and gas tariffs (with state-owned company EDF absorbing the costs), and Germany earmarked more than €300 billion to shield its domestic consumers from high energy bills (using its huge financial firepower).

The EU’s energy crisis response was also incoherent in its aims and insufficient in its results. For instance, the EU agreed to put in place a revenue cap of at least €180/MWh on so-called infra-marginal producers (e.g., wind farms or nuclear plants), potentially undermining investor confidence at a time when Europe needs to roll out renewables as soon as possible. At the same time, EU leaders introduced a wholesale gas price cap of €180/MWh which contains so many safeguards that skeptics denounce it as a political illusion. The EU also created an Energy Platform to facilitate joint purchasing of natural gas, yet individual member states continue to pursue bilateral gas deals with foreign suppliers (even if a new regulation now requires that at least 15% of gas storage is filled through joint purchases in 2023).

Concluding thoughts

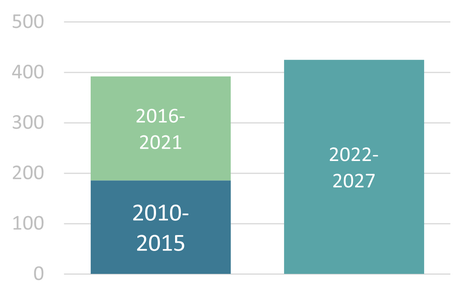

Europe is facing a longer-term energy crisis that requires a mid-term and long-term plan, rather than simply addressing emergencies on a winter-by-winter basis. Fortunately, the European Green Deal and its accompanying policy packages, such as the 'Fit for 55' initiative, offer a roadmap for transitioning to a more sustainable energy future. Despite some positive developments, such as the EU's projected addition of 50-60GW of renewable capacity this year and the prospect of adding more renewable capacity in the next five years than the previous decade (Figure 7), there are also concerning trends, such as the rush to build new natural gas and LNG connections and conclude new LNG supply deals, which could lock in gas infrastructure that conflicts with the EU’s climate goals. It is crucial that the EU remains committed to the European Green Deal since it is the only effective solution to address the ongoing energy crisis.

Figure 7. Renewable capacity additions, Europe (GW/year)[24]

Footnotes

[a] Notes: EU aid to Ukraine covers bilateral commitments from EU members and institutions from Jan. 24 to Nov. 20, 2022. Does not include private donations and support for refugees outside of Ukraine. EU payments to Russia for fossil fuels covers seaborne, pipeline and railway shipments of crude oil, oil products, natural gas, LNG and coal from Feb. 24 to Dec. 16, 2022.

[b] Blue denotes pipeline deliveries, green denotes LNG.

Endnotes

[1] ICE, “Dutch TTF Natural Gas Futures”, https://www.theice.com

[2] Gas Infrastructure Europe, “Storage database”, https://www.gie.eu/transparency/databases/storage-database/

[3] Nikos Tsafos, Twitter post. November 3, 2022.

[4] IEA, Gas Market Report, Q4-2022 (Paris: IEA/OECD, October 2022).

[5] IEA, How to Avoid Gas Shortages in the European Union in 2023 (Paris: IEA/OECD, December 2022).

[6] Ben McWilliams and Georg Zachmann, "European natural gas demand tracker,” Bruegel Datasets, first published December 7, 2022, https://www.bruegel.org/dataset/european-natural-gas-demand-tracker

[7] John Kemp, “Column: Europe should thank mild autumn for averting gas crisis this winter,” Reuters, December 19, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/article/europe-gas-kemp-idUSL1N3361IH

[8] Martin Sandbu, “What energy crisis? European industry is showing its adaptability,” Financial Times, December 1, 2022.

[9] Nikos Tsafos, Twitter post. November 3, 2022.

[10] Eurostat, “Imports of natural gas by partner country - monthly data”, Eurostat, December 19, 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/NRG_TI_GASM/default.

[11] Fatih Birol, “Coordinated actions across Europe are essential to prevent a major gas crunch: Here are 5 immediate measures,” IEA Commentary, July 18, 2022, https://www.iea.org/commentaries/coordinated-actions-across-europe-are-essential-to-prevent-a-major-gas-crunch-here-are-5-immediate-measures

[12] Arianne Antezza et al., "The Ukraine Support Tracker: Which countries help Ukraine and how?,” Kiel Working Paper 2218, 2022; CREA, “Financing Putin’s war: Fossil fuel imports from Russia during the invasion of Ukraine,” 2022, https://energyandcleanair.org/financing-putins-war/

[13] European Commission, “REPowerEU: A plan to rapidly reduce dependence on Russian fossil fuels and fast forward the green transition,” European Commission, May 18, 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_3131

[14] IEA, A 10-Point Plan to Reduce the European Union’s Reliance on Russian Natural Gas (Paris: IEA/OECD, March 2022).

[15] IEA, How to Avoid Gas Shortages in the European Union in 2023 (Paris: IEA/OECD, December 2022).

[16]Bozorgmehr Sharafedin, “European gas storage on track to meet target but at a cost,” Reuters, August 4, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/european-gas-storage-track-meet-target-cost-2022-08-04/

[17] “Europe’s $1 Trillion Energy Bill Only Marks Start of the Crisis,” Bloomberg, December 18, 2022.

[18] Giovanni Sgaravattik, Simone Tagliapietra and Georg Zachmann, “National policies to shield consumers from rising energy prices”, Bruegel Datasets, November 29, 2022, https://www.bruegel.org/dataset/national-policies-shield-consumers-rising-energy-prices.

[19] Greg Molnar, ‘Turning East: How fast can Russia divert its gas supplies away from Europe to Asia?’ LinkedIn post, 2022, https://www.linkedin.com/posts/greg-moln%C3%A1r-38601171_gas-lng-russia-activity-6931859734513762304-XAm1; Nikos Tsafos, “Can Russia Execute a Gas Pivot to Asia?,” CSIS Commentary, May 4, 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/can-russia-execute-gas-pivot-asia.

[20] For a different perspective, see: Javier Blas, “Can Europe’s Energy Bridge to Russia Ever Be Rebuilt?,” Bloomberg, December 12, 2022.

[21] Andreas Goldthau and Nick Sitter, A liberal actor in a realist world: The European Union regulatory state and the global political economy of energy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015).

[22] Council Regulation (EU) 2022/1369 on coordinated demand for gas, August 8, 2022.

[23] Council Regulation (EU) 2022/1854 on an emergency intervention to address high energy prices, October 7, 2022

[24] IEA, Renewables 2022 (Paris: IEA/OECD, December 2022).