The Construction of Europe

By Eline Ruëll

Promoted by Prof. dr. Hendrik Vos

[February 2024]

In its relentless quest for greater legitimacy, the European Union expects much from the promotion of a ‘European identity’. Academics and other intellectuals have written extensively on this subject. But contributions on this foggy concept quickly become an essentialist search for the core of ‘Europe’.

Europe is a social construct that can be assigned different meanings. Consequently, the aim of this research cannot be to ascertain the veracity of representations of Europe. However, their constructed character can be exposed and their use and occurrence in a particular social artefact can be mapped out. Research on constructions of Europe is not new, but so far education has been largely overlooked.

The main aim of this research is to generate qualitative insights into how different constructions of Europe emerge in empirical data, through a systematic content analysis of educational content.

In addition, by analysing both older and more recent sources, this research provides a first impetus to study the way in which constructions of Europe have evolved over time. Since, how Europe is represented depends on its cultural and historical context.[1]

Finally, based on both theoretical and empirical insights, a new conceptual framework is developed to analyse constructions of Europe. This theoretical framework will help to structure the multitude of meanings, that Europe evokes, and can be useful for further research.

Literature Review

‘Europe’ attracts political and academic attention

Political interest in constructing a ‘European identity’ grew over the years.[2] The European identity issue also manages to attract the attention of various academic disciplines[3] and makes a frequent appearance in public debates.[4] But why does a so-called European identity matter to European politics, and those who study it?

Political institutions need the support of those in whose name they govern.[5] Yet the systematic expansion of the EU’s competences has not been accompanied by an increase in public support and legitimacy.[6] This fuelled the debate about a so-called democratic deficit.[7]

A democratic Europe needs a community that gives it legitimacy. This is the central argument of the so-called demos-thesis.[8] Many academics consider a collective identity a necessary condition for the functioning and survival of a democratic political system. [9] The more competences the EU gets, the more dependent it becomes on the diffuse support of its citizens.[10] A collective identity should ensure support for a political project, even if it does not bring immediate benefits.[11] The lack of such a European demos, would be pernicious for the democratic character and legitimacy of the EU.[12]

Not only the search for legitimacy explains the interest in the idea of Europe. In the context of EU enlargement, for example, the ‘Europeanness’ of some candidate countries is disputed.[13] According to Article 49 TEU, ‘any European State which respects the values referred to in Article 2 and is committed to promoting them may apply to become a member of the Union’. But what is a European state and where do the borders of Europe lie?[14]

Furthermore, the concept of European identity surfaces in relation to the future of European social policy. If the EU is ever to pursue redistributive policies, a minimal collective identity is necessary.[15]

Finally, it is interesting for academics to study the idea of Europe, simply because promoting a European identity is considered relevant, or even necessary by EU policy makers.[16]

What is Europe?

Europe does not exist.[17] It is a social construct[18], a so-called imagined community in the words of Benedict Anderson.[19] Unlike ‘brute facts’, Europe is an ‘institutional fact’, which cannot exist independently of perception or language.[20]

Europe is an empty signifier, that can be interpreted in a variety of ways.[21] In one breath, it mobilises a broad amalgam of different thought categories.[22] ‘Europe’ can be imagined as a progressive project or a superpower in decline, a Christian society with certain cultural traditions or a liberal value community, a geographically defined area or a political entity that can expand.[23] These cultural, geographical, economic or political meanings of Europe each tell a different story and cannot be reduced to one another. Contrary to the ideal of the nation-state, Europe’s cultural, economic and political boundaries do not coincide.[24]

These constructivist starting points bring us to the Idea of multiple Europes.[25] Whether they call it ideas, stories, images, projections, representations, constructions, Eurotypes or types of Europe, this idea recurs among several authors.

Getting a grip on the idea of Europe, and all its different, contradictory and changing meanings, is a complex challenge, but is not entirely impossible.[26]

The idea of Europe is not static but enormously complex and flexible.[27] It is constantly being invented and reinvented, constructed and reconstructed.[28] A wide range of different, competing, overlapping, constructions of Europe constantly interact with each other.[29]

How Europe is represented depends on historical context. The logical consequence is that which constructions of Europe are dominant changes.[30] Over time, the boundaries of Europe shifted[31] and they cannot be unambiguously defined to this day.[32] Constructing Europe has a long history, with different constructions from different periods leaving their traces.[33] The constructions of Europe that are prevalent today are the result of a dialectical process, in which different ideas become intertwined.[34]

Getting a grip on a multitude of Europes

Identifying various constructions

Which different ideas about Europe exist? Some authors identify a range of different constructions of Europe.

Based on insights from imagology, a cultural-historical specialism that studies images of national characters, literary scholar and historian Joep Leerssen identifies a series of ‘Eurotypes’ throughout history.[35] In Konstruktionen von Europa, Gudrun Quenzel distinguishes 11 different basic conceptions of Europe, including, for example, Europe as a continent, Christian homeland, a civilisation of technological progress or a negative memory community.[36] The word Europe is often used as a seemingly objective geographical concept. The idea of Europe as a continent appears scientific and neutral at first glance, but it is anything but neutral or purely geographical. As mentioned earlier, the borders of the European continent shifted throughout history and the demarcation of geographical borders proved to go hand in hand with cultural and political meanings.[37] Delanty (1995) keeps it at five discourses on the idea of Europe. He too identifies a Christianity discourse and a civilisation discourse.

Other authors developed more simple theoretical approaches. They try to capture the many constructions of Europe in a simple dichotomy or tripartite division. For example, authors often make a distinction between a Europe defined in cultural terms, on the one hand, and a Europe defined in political terms, on the other.

A cultural Europe

Philosophical historian Luuk van Middelaar[38] identifies a ‘cultural outer sphere’, which finds its demarcation in geography and history. German political scientist Thomas Risse[39] also talks about a cultural Europe in A Community of Europeans. He calls it a ‘traditional European identity’. Here, Europe is defined in cultural terms as a western, Christian civilisation of white people with a common history, strong national traditions and clear geographical borders. ‘The Other’ are non-European migrants, non-Christian countries and Muslims.[40] Some of the eurotypes described by Leerssen[41] are similar to Risse’s traditional Europe.

According to sociologist Monica Sassatelli[42] the many ideas about a cultural Europe cluster around one all-encompassing dichotomy: unity and homogeneity versus fragmentation and diversity. In Sassatelli’s model, the unity in diversity idea transcends as a third category the dichotomy between unity and diversity, as a dialectical synthesis. Others are more critical. According to Shore[43] the unity in diversity slogan cannot adequately address the fundamental contradiction between the idea of Europe as a union among the ‘peoples of Europe’, in the plural and the idea of an integration process leading to one ‘European people’. Shore[44] is clear: "the goal is not diversity but unity". As Delanty notes, the slogan is unity in diversity, not unity and diversity.[45]

A political Europe

Besides the ‘cultural outer sphere’, van Middelaar distinguishes a ‘political inner sphere’, which refers to the ‘European project’ of which a treaty forms the basis. Using the spheres metaphor, van Middelaar points to the shift in the use of the word ‘European’ since the interwar period.[46] Before that period, the word ‘Europeans’, referred to the inhabitants of a particular continent. Later, ‘Europeans’ was increasingly used to refer merely to European political circles. Europe moved from the cultural outer sphere to the institutional inner sphere. Because the leaders of the European project think they need the support of the ‘European people’, they want to partially remove ‘Europe’ and the ‘European’ from that inner sphere, which has happened to some extent according to van Middelaar.

Not only van Middelaar, but also Risse contrasts his ‘traditional cultural Europe’ with a ‘modern political Europe’.[47] He based his theory on the work of Michael Bruter, which showed that people systematically distinguish between a cultural and political dimension of Europe.[48] Risse speaks of a modern, secular and cosmopolitan identity. This identity is founded on enlightenment values such as peace, democracy and human rights. Whereas traditional Europe is defined in cultural terms, Risse describes modern Europe as an EU-Europe. ‘The Other’ of this modern political Europe are xenophobia, racism and the history of the European continent, characterised by militarism and nationalism.[49]

That idea of a community based on liberal and cosmopolitan values also recurs among political philosophers.[50] What Risse describes as a modern political Europe is reminiscent of Jürgen Habermas’s ‘constitutional patriotism’, which points to a shared loyalty towards certain political values, such as freedom, equality and democracy. This way, a post-national political community would emerge that is not based on a shared cultural identity but rather recognises cultural differences.[51]

While Risse’s dichotomy provides interesting insights, a first look at the data makes it clear that a dichotomy between a traditional cultural Europe and a cosmopolitan political Europe would be an oversimplified starting point.

A third Europe?

The distinction between a Europe in cultural terms and a Europe in political terms seems to be a recurring element. But a first look at the data makes one wonder whether a distinction between a cultural and political Europe is sufficient. There is need for a third category: an economic Europe. The theoretical framework is explained further on p. 7.

The identity politics of the European Union

In need of a new story?

In European circles, a lack of public support is seen as a major obstruction to the integration project.[52] Fostering a European identity is seen as the answer to that so-called democratic deficit and the EU’s legitimacy crisis.[53] In other words, there is an important link between policy, the construction of a particular identity and power.[54]

According to some, the narrative of the common market, that of an economic Europe, is not enough to create a strong community.[55] Europe would need a different story[56]: that of a political Europe or more so that of a cultural Europe.

“It needs more, a story which tells people that they are citizens of a political community. And maybe it even needs a still stronger identity since it must generate a sense of a particular responsibility and recognition of the other European citizens which goes beyond recognizing them as co-citizens”.[57]

A task for education- and cultural policy

A first important step in the ‘turn towards identity’ was taken in 1973 at the Copenhagen Summit, when the leaders of the then nine member states, signed a Declaration on European Identity.[58] In the 1980s, the Adonnino Committee was commissioned to think about how to bring Europe closer to its citizens.[59] The committee published two reports with a series of concrete measures to promote the idea of Europe. These included giving the European union its own logo, flag, anthem and public holiday. The committee also proposed to work on a European passport and driving licence, a European Olympic team, youth exchange programmes and a stronger European dimension in education.

Promoting a European identity became primarily a task for cultural and educational policies[60], within which several projects were launched. The constructive character of cultural initiatives, such as the House of European History[61], the European Heritage Label[62] and the Capitals of Culture[63] has been analysed more than once. Conceptions of ‘Europe’ and ‘European identity’ in policy documents on culture[64] and education[65] have also been examined.

In her research on how European identity was represented in EU education policy, Arkan[66] detected an evolution. In the beginning, policy documents mainly referred to the promotion of a cultural European identity, founded on a certain ‘civilisation’, and common heritage. In the 1990s, attention shifted towards a more political interpretation of European identity. The emphasis came to lie on EU citizenship, which had just been created by the Maastricht Treaty, and certain political values.

Quite some research has been done on how ‘Europe’ is constructed in EU policy documents. However, until now, there has hardly been any research on which ideas of Europe have been and are being put forward in educational practice.

Research Question

The functioning of the European Union as a sustainable, legitimate and democratic political system is often associated with the need for a European community that identifies itself as such. Research on such a so-called European identity is mostly limited to quantitative methods.[67] Surveys and statistical analyses are for instance used to examine the extent to which individuals identify with Europe or with the EU. This way, the content of a ‘European identity’, or the meanings that ‘Europe’ evokes, remain hidden behind figures and bar charts.

Research on which constructions of Europe circulate in social artefacts is not new. The way in which Europe is put forward in certain cultural initiatives[68], policy documents[69] or literature[70] has already been examined. But how Europe is represented in education remains mostly overlooked.

That representations of Europe in educational content have hardly been explored until now is remarkable. After all, the comparison with how nation states in the 19th century relied on education as a crucial tool to create a sense of community is easily made.[71] So even in the light of a possible strengthening of a European sense of community, it is interesting to explore how Europe is constructed in educational content.

Starting from the constructivist premise that Europe is an empty signifier that can be interpreted in diverse, and even contradictory, ways, this research attempts to generate qualitative insights into how different constructions of Europe emerge in practice. It focuses on a specific social artefact: educational content.

Research question 1: How is Europe constructed in educational content?

The aim here is not to check the veracity of particular constructions or to look for some kind of core Europe. The intention is to expose their constructed nature and to identify the use and occurrence of certain ideas about Europe.

Dominant constructions of Europe change over time. [72] This research aims to analyse whether there is a certain evolution in how Europe is constructed in educational content.

Research question 2: How did constructions of Europe in educational content evolve over time?

Finally, throughout this research, a new conceptual framework is developed. This framework can be useful to analyse types of constructions of Europe in other social artefacts in further scientific research. The basis of this conceptual framework is outlined in the ‘theoretical framework’ section.

Research question 3: How can we better understand the multiplicity of constructions of Europe in a theoretical framework?

Theoretical Framework

What is Europe and what ideas about Europe exist? In the literature, the answers to these questions vary. Theories have similarities but also place different emphases and concepts such as culture, politics, citizenship, modern, traditional are given different meanings. The challenge is to integrate these theories into a new conceptual framework relevant to this research: the idea of Europe in educational content.

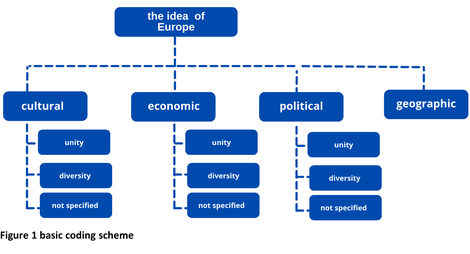

Many theories make a distinction between a cultural and political Europe. To this an economic and geographical category is added. A geographical, cultural, economic and political construction of Europe are the main categories of the theoretical framework or coding scheme. This division is interesting because these constructions, and the imagined boundaries they evoke, cannot be reduced to one another.[73]

Sassatelli’s dichotomy between unity and diversity tackles cultural ideas of Europe. Yet it may be interesting to apply them to the economic and political dimensions as well. This distinction is added as a second layer to the coding scheme. Under each main category, the distinction between unity and diversity is made. For instance, if Europe is defined in cultural terms, is the emphasis on unity, by emphasising a common history, for example? Or instead on diversity, by bringing out national stereotypes? A residual category ‘not specified’ refers to segments where the emphasis is neither on unity nor on diversity, or it is not clear.

This scheme forms the basis of the empirical analysis (Figure 1).

Research Design

Since this study will analyse certain social artefacts, educational content, the choice for a content analysis is obvious. This method reduces content to manageable categories or codes. A coding scheme guides the analysis and allows one to discover patterns and extract meanings from the data, without relying on intuition (Figure 1). To achieve an in-depth analysis this research adopts a more qualitative approach. To ensure a systematic approach, the analysis is carried out using the coding programme Nvivo.

This research focuses exclusively on Dutch educational content intended for Flemish primary or secondary education. Furthermore, the research is delimited in time. The availability of sources plays a decisive role here: the first usable source dates from 1958 and the last from 2023. The analysed educational content can include textbooks, workbooks, brochures and so on. Simply put, textual sources that can be used in a school environment.

In terms of content, the study focuses solely on sources with ‘Europe’ as its main subject. Sources that are less explicitly about ‘Europe’, but which also contain certain constructs of Europe, are therefore not considered. Content on the European Union can, however, be included in the study, provided there is some kind of ‘conceptual confusion’ between ‘Europe’ and the ‘European Union’[a], and the material goes beyond a dry explanation of how the institutions work.

The data are mainly collected through libraries and their archives. The majority comes from the archive of the Royal Library of Brussels. Content from the EU Learning Corner, a digital platform where the European Union itself offers educational content on ‘Europe’, was also analysed.

In total, twenty-nine sources were analysed. About 1/3rd date from the twentieth century. The other part was published after the turn of the century. The sources are often publications by the main publishers of educational content in Flanders: Plantyn, Van In, Averbode and Pelckmans.

The coding scheme was drawn up based on both a deductive and inductive logic. On the one hand, the coding scheme is based on different theories about ‘types of Europe’. However, these theories are integrated into the coding scheme in such a way that the scheme cannot be traced back to any specific theory or author. On the other hand, the broader deductive framework is adapted to the data. There is room to inductively identify codes. Throughout the research process, based on an open coding process, subcodes are added.

Empirical Findings

Europe in class

Research question 1: How is Europe constructed in educational content?

How does educational content answer the question ‘What is Europe’? What constructs of Europe circulate in textbooks? What ideas about Europe were, and are, taught in Flemish schools?

We can divide constructions of Europe into four dimensions: a geographical, cultural, economic and political dimension. All four dimensions are present in the content analysed. Figure 2 shows the occurrence of the codes based on the number of references to a given code.

Geographic dimension

The geographic dimension contains descriptions of Europe as ‘a peninsula of Asia’, or ‘a small continent’. A significant proportion of the analysed texts represent Europe, often in the first paragraphs, in geographical terms. This dimension contains, however, the fewest references (58 attributed codes). This is not surprising because you cannot endlessly elaborate on a geographical description.

The idea that Europe is an objective geographical concept has already been critically reflected on in the literature review.

Cultural dimension

Second, Europe can be represented as ‘something cultural’ (431 assigned codes) (Figure 3).

Cultural unity

On the one hand, constructs depicting Europe as a cultural unit emerge (found in 28 of the 29 sources). Within this category, several subcategories were identified.

The most important subcategory in this regard is the idea of ‘a European history’, which in turn can be broken down into further subcategories.

The core of that European past is often described with words like war, conflict, violence and bloodshed. At first glance, war and conflict seem contradictory to the category ‘cultural unity’. Yet, at the root of such references lies the idea that there is such a thing as the European past. That that past is characterised by wars and violence does not alter the matter.

It is eminently applicable to references to the two World Wars. The horror of World War II is, almost without exception, used as a stepping stone to discuss Europe’s economic and political integration. It is, as it were, the origin myth of the European Union. ‘After the war, the Europeans would work together to ensure prosperity and peace’. These ideas were respectively coded under the economic and political dimensions and will be discussed later. Besides the two world wars, the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 is also considered as one of the milestones in European history. Sometimes the search for this common past goes further back in time: to the Greeks and Romans, for example and occasionally, some historical figures are mentioned, such as Charlemagne, Charles V or Napoleon.

Related to the idea of a common past is the idea of Europe as the cradle of ‘Western civilisation’, which is said to consist of two components, art and science. The idea that ‘modern civilisation’ originated in Europe cannot only be found in the oldest textbooks. It can be found up until 2007.

A third important subcategory covers the European symbols created in the 1980s, such as the flag and anthem.

Other subcategories include ‘art and culture’, referring to the way Europeans are united today by watching the same television programmes or reading the same books, ‘cultural projects’, ‘Christianity’ and ‘white’.

Cultural diversity

On the other hand, the cultural diversity of Europe can be stressed. There are different cultures, customs, habits, traditions, religions and languages.

Some textbooks present Europe’s cultural diversity as an ‘asset’, a ‘strength’ or "richness" that makes Europe ‘unique’. Such representations lean towards the unity in diversity slogan, which blurs the line between unity and diversity. The question is whether we can truly speak of diversity discourse if that diversity is in function of a uniqueness discourse.

Cultural, unspecified

Finally, a third subdivision contains all the cultural representations of Europe where the emphasis is neither on unity nor diversity, or it is not clear. It consists mainly of images of typical dishes, monuments and other tourist attractions. On the one hand, they are stereotypical national symbols, which could point to Europe’s cultural diversity. On the other hand, they can also, especially when depicted together, point to a cultural unity. When the author’s purpose is unclear and the context is not decisive, these codes fall into this category.

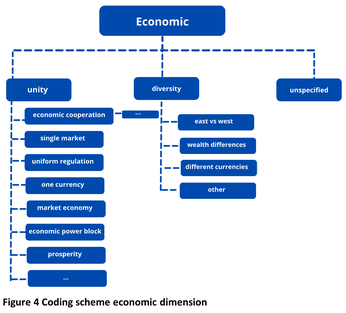

Economic dimension

Third, Europe can be represented in economic terms (428 assigned codes) (Figure 4).

Economic unity

Again, we can define several subcategories. One way to represent Europe as an economic unity is to talk about economic cooperation, such as the ECSC, EEC and Euratom, under de heading of ‘Europe’.

Another important subcategory is the ‘common market’, with free movement of goods, services, people and capital (Image 1). As a result, there is a lot of uniform regulation regarding the products traded in that single market. Moreover, there is a common currency (Image 2) and Europe is united by its prosperity, or at least the common pursuit of it. Other subcategories include ‘market economy’, ‘economic power block’, ‘economic policy’ and ‘transport’.

Economic diversity

Europe is not always presented as economically united. On the contrary, sometimes economic divisions are emphasised, although such constructions remain very limited. In this case textbooks mention the contrasts between east and west, differences in wealth or the fact that not all ‘European’ countries use the euro.

Economic, unspecified

The category ‘economic - unspecified’ is a residual category that brings ‘Europe’ in the economic sphere, with no clear emphasis on unity (or diversity). However, it contains so few codes that it loses its relevance.

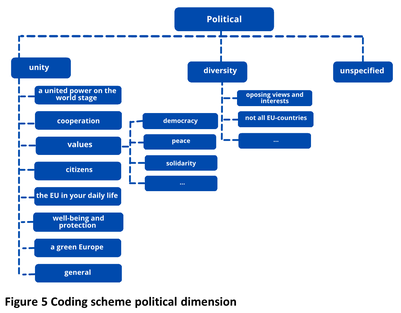

Political dimension

Finally, there is a political Europe. Based on the number of references, the political dimension is the most present (662 assigned codes) (Figure 5). Here, ‘Europe’ and the ‘European Union’ are often used as synonyms.[b]

Political unity

As within the cultural and economic dimension, the ‘unity’ category far outweighs the other two categories.

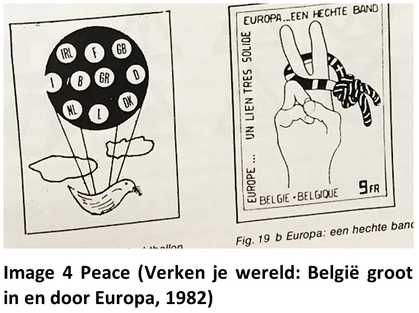

The absolute outlier in this category is the European-values discourse, with a staggering 291 references and present in 83% of the analysed educational sources. Again, we can discern further subcodes. Nine ‘values’ were identified based on the data: peace, democracy, the rule of law, freedom, equality and non-discrimination, human rights, human dignity and respect, solidarity and tolerance. Not surprisingly, as it is a crucial part of the EU’s founding myth, peace is the most common value mentioned along with democratic ideals (Image 3 and 4).

The other subcategories of ‘political unity’ are: ‘a united power on the world stage’, ‘cooperation’, ‘citizens’, ‘the EU in your daily life’, ‘well-being and protection’ and a ‘green Europe’.

Political diversity

Representations of Europe as politically divided are less common. They can take on different forms, such as: ‘east vs west’, ‘different political organisation’, ‘differing regulation’, ‘opposing views and interests’, ‘no strong value-community and ‘not all EU-countries’.

Political, unspecified

Sometimes it is unclear or debatable whether a code belongs to ‘unity’ or ‘diversity’. Within this last category Europe is represented as something political, but whether there is unity or rather diversity and division within that political ‘thing’ is not clear.

Unity, diversity or both?

Within the dimensions discussed earlier, we further distinguish between constructions that emphasise unity or diversity[c]. There is also a residual category ‘not specified’ for when a code fits neither, or it is not clear.

As became clear above, constructions that emphasise unity prevail. Therefore, the unity categories are theoretically developed best. Although a distinction between unity and diversity, as a second layer in the coding scheme, proved its relevance, the diversity categories and residual categories are less well-developed.

When constructions of diversity emerge in texts, it is striking how authors will still try to maintain a balance between unity on the one hand and diversity on the other. This balancing act sometimes results in the appearance of the ‘unity in diversity’ slogan, the official motto of the European Union. It pops up mainly in educational content offered by the EU itself. But as mentioned earlier, we can cast a critical light on the extent to which the unity in diversity idea actually maintains a balance between the two. After all, unity lies precisely in diversity. In other words, the balance tilts towards unity rather than diversity.

Euro-propaganda and critical reflection

Answering the question "What is Europe?" is no easy task. But perhaps the divergent answers to the what-is-Europe question are not the most important. What matters most is the idea that Europe is something that exists. Above all the obviousness and self-evidence with which ‘Europe’ is talked about, is important.

That self-evidence with which ‘Europe’ is being talked about can vary greatly. Some textbooks contain outright ‘Euro-propaganda’. Europe is like a country, to which you belong! We belong together, like one big family! Not surprisingly, these slogans can be found in EU-sponsored material. But other textbooks do not shy away from a dash of Euro patriotism either. Others are more reflective. As in this paper, they recognise that ‘Europe’ has no single definition but can evoke different meanings. Europe’s borders, even seemingly objective geographical borders, are not fixed.

Europe throughout history

Research question 2: How did constructions of Europe in educational content evolve over time?

Which constructs of Europe are dominant may evolve over time.[74] Can we detect an evolution, based on the theoretical framework, in the way Europe is represented in educational content?

More and more Europe

It is striking how, regardless of how Europe is presented, ‘Europe’ is increasingly covered in textbooks. Although older textbooks on ‘Europe’ exist, they are more omnipresent after the turn of the century. ‘Europe’ is often given its own chapter or even an entire thematic textbook.

Looking at the number of codes in relative terms, we can see that, over time, proportionally more codes are assigned to the political dimension than the cultural and economic dimensions. One could therefore argue that how Europe is represented follows the course of European integration: it started in the economic domain, and then moved increasingly into the political sphere. Although we cannot state that political representations of Europe have completely dispelled cultural and economic representations of Europe. Both a Europe defined in cultural terms and in economic terms, remain present in educational sources. In other words, if we look purely at the level of the main categories of the coding scheme, the four dimensions, there is no striking evolution noticeable. At the second level, the distinction between unity and division, no outspoken shift takes place either. The category unity is dominant in all dimensions, and this has not changed over the years.

From ‘white’ to a common heritage

Only when we look at specific subcategories do we get a better idea of how representations of Europe have evolved. The idea that Europe consists mainly of ‘whites’, for example, only appears in the oldest textbooks. The ‘Euro-citizens’ that appear in recent textbooks on the other hand tend to have different skin colours.

Representations of Europe as a cultural community with a common past made inroads in the early 1990s. Up to 2010, references to a common history are very strong. After that, they still occur regularly, although to a lesser extent.

In contrast, the idea that ‘Western civilisation’ originated in Europe and that Europe is the cradle of art and science seems to have passed its time. There, too, we see coding references peak around the late 2000s. But after 2010, that civilisational thinking disappears.

More and more European values

Since the 1980s, a political Europe has become increasingly common. Especially between 2003 and 2010, political constructs of Europe, in all its various forms, are a regular feature. This increase is mainly due to the rise of the ‘European values discourse’. Since the turn of the century, the peace narrative has been complemented by a variety of other ‘European values’, such as ‘democracy’ and ‘solidarity’. The idea that Europe is a political community based on certain values is especially strong in educational content sponsored or offered by the European Union.

These results are largely in line with the evolution, detected by Arkan[75] in EU policy documents on education (see earlier on p. 5). Her research showed that, from the 1990s onwards, policy documents gave a more political interpretation of a ‘European identity’.

Towards a new analytical framework?

Research question 3: How can we better understand the multiplicity of constructions of Europe in a theoretical framework?

Europe seems to evoke an overwhelming cacophony of meanings. Yet it is possible to structure this multitude of meanings and ideas. Based on both insights from literature and empirical data, a new theoretical framework was developed to analyse constructions of Europe in a particular social artefact.

The analytical framework distinguishes between 4 dimensions: a geographic, cultural, economic and political dimension. This theoretical basis proved to be a useful starting point for the analysis of educational content. Within the cultural, economic and political dimensions, a further distinction was made between unity and diversity. This also proved to be an applicable distinction. But because most representations of Europe fit within a ‘unity category’, and the unity categories are theoretically best developed, the relevance of this second layer in the coding scheme can be questioned. Whether this new analytical framework is also relevant for the analysis of other social artefacts will have to be proven by further research. But the theoretical basis seems promising.

Conclusion

In the lingering quest for legitimacy, the European Union believes it would do well to promote a ‘European identity’. But that is easier said than done. Soon, the difficult questions pile up. What might this ‘European identity’ look like? Who defines it? What should be the basis of a European sense of community? Down to the existential ‘What is Europe?’

The what-is-Europe question seems like an eternal intellectual challenge. This research breathes new life into the academic and political debate by examining what conceptions of ‘Europe’ were and are being taught in educational practice. Twenty-nine Flemish educational sources, from 1958 to 2023, were analysed.

It is hard to get a grip on the concept ‘Europe’. It evokes different, sometimes contrasting, meanings. Yet this research, based on an interaction between theoretical and empirical insights, worked out an analytical framework that helps us structure these different meanings. That analytical framework contains four dimensions, four ‘types’ of Europe: a geographical, cultural, economic and political Europe. Within three dimensions, we can make a further distinction between constructions that emphasise unity, or diversity, though in all dimensions the category unity prevails.

Using further subcategories, this study uncovers how different representations of Europe take shape. The cultural dimension for example contains many references to ‘a common European past’. Within the economic dimension, the subcategory ‘single market’ stands out. And in the political dimension, the idea that ‘Europe’ is a community bounded by certain political values leads the way.

Some textbooks, whether they are released with EU support or not, are not afraid to stir up the love for Europe with catchy slogans. Other books take a more critical stance and dare to ask the question: ‘What even is Europe?’

Moreover, by analysing both recent material (2023) and older sources (from 1958 onwards), this study examines how the construct of ‘Europe’ has evolved in education. While there was no remarkable shift at the level of the four dimensions, evolutions are noticeable at the level of the subcategories. The idea that Europe only consists of ‘whites’, for example, is only present in the oldest textbooks. While the European values discourse, which made its entrance at the end of the twentieth century, is omnipresent in contemporary educational content.

Footnotes

[a] “Conceptual confusion between Europe and the European Union” does not refer to a misuse of words as if the two concepts carry a clear universal meaning, but rather that the two words are used interchangeably in the source.

[b] Some authors choose to make a strict theoretical distinction between the ‘EU’ and ‘Europe’. Precisely because the two terms are used interchangeably and evoke common meanings, this paper deliberately does not do so.

[c] No further distinction between unity and diversity was made within the geographic dimension.

Endnotes

[1] Klaus Eder, “A theory of collective identity making sense of the debate on a ‘European identity,” European journal of social theory 12, no. 4 (2009): 427-447. Joep Leerssen, “Eurotypes after Eurocentrism: Mixed Feelings in an Uncomfortable World,” The Idea of Europe (2021): 85–98.

[2] Cris Shore, “Inventing the ‘People’s Europe’: Critical Approaches to European Community ‘Cultural Policy,” Man 28, no. 4 (1993): 784.

[3] Nico Carpentier, “The European Assemblage: A Discursive-Material Analysis of European Identity, Europaneity and Europeanisation,” Filosofija. Sociologija 32, no. 3 (2021): 231.

[4] Eder, “A Theory of Collective Identity,” 428.

[5] Viktoria Kaina, “European identity, legitimacy, and trust: conceptual considerations and perspectives on empirical research,” European identity: theoretical perspectives and empirical insights (2006): 115; Cris Shore, “In uno plures’(?) EU Cultural Policy and the Governance of Europe,” Cultural Analysis, 5, no. 5 (2006): 11.

[6] Percy B. Lehning, “European Citizenship: Towards a European Identity?,” Law and Philosophy 20, no. 3 (2001): 240; Cris Shore, “In uno plures’(?),” 11.

[7] Kaina, “European identity, legitimacy, and trust,”116; Wolfram Kaiser and Richard McMahon, “Narrating European Integration: Transnational Actors and Stories,” National Identities 19, no. 2 (2017): 151; Shore, “Inventing the ‘People’s Europe’,” 785; Shore, “In uno plures’(?),” 11.

[8] Eder, “A Theory of Collective Identity,” 434; Gudrun Quenzel, “Konstruktionen von Europa : Die europäische Identität und die Kulturpolitik der Europäischen Union,” (2005): 10.

[9] Kaina, “European identity, legitimacy, and trust,”113-146; Quenzel, “Konstruktionen von Europa,”; Thomas Risse, A Community of Europeans?: Transnational Identities and Public Spheres (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010).

[10] Kaina, “European identity, legitimacy, and trust,”116.

[11] Eder, “A Theory of Collective Identity,” 434.

[12] Eder, “A Theory of Collective Identity,” 434; Kaina, “European identity, legitimacy, and trust,” 113- 146.

[13] Michaela Ferencová; “Reframing identities: some theoretical remarks on ‘European identity building,” International Issues & Slovak Foreign Policy Affairs 15, no. 01 (2006): 4.

[14] Shore, “Inventing the ‘People’s Europe’,” 786.

[15] Victoria Kaina & Ireneusz Paweł Karolewski, “European Identity Theoretical Perspectives and Empirical Insights,” (Berlin: Lit, 2006): 12; Patrick Loobuyck, “Een gedeelde Europese identiteit: noodzakelijkheid en (on) mogelijkheid,” Samenleving en politiek 15, no.10 (2008): 37-44; Quenzel, “Konstruktionen von Europa,” 10; Risse, A Community of Europeans, 8.

[16] Shore, “Inventing the ‘People’s Europe’,” 779-800.

[17] Ulrich Beck, Edgar Grande, and Ciaran Cronin, Cosmopolitan Europe (Cambridge: Polity, 2008): 6; Jeffrey T. Checkel & Peter J. Katzenstein, “European identity,” (Cambridge University Press, 2009); Joep Leerssen, Spiegelpaleis Europa: Europese cultuur als mythe en beeldvorming (Nijmegen: Vantilt, 2011), 7; Joep Leerssen, “Stranger/Europe,” Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Philologica 9, no. 2 (2017): 7; Francesco Mangiapane & Tiziana Migliore, Images of Europe: The Union Between Federation and Separation (Cham: Springer, 2021).

[18] Gerald Delanty, Inventing Europe: Idea, Identity, Reality (London: Macmillan, 1995): 1; Ferencová; “Reframing identities,” 5; Shore, “Inventing the ‘People’s Europe’,” 781; Bo Stråth, “A European Identity,” European Journal of Social Theory 5, no. 4 (2002): 387–401.

[19] Carpentier, “The European Assemblage,” 232; Ferencová; “Reframing identities,” 7; Risse, A Community of Europeans, 7, 22-23.

[20] Luuk van Middelaar, De passage naar Europa: geschiedenis van een begin (Groningen: Historische uitgeverij, 2009), 294-295; Astrid Van Weyenberg, “‘Europe’ on Display: A Postcolonial Reading of the House of European History,” Politique Européenne 66, no. 4 (2020): 46.

[21] Carpentier, “The European Assemblage,” 232; Eder, “A Theory of Collective Identity,” 435; Quenzel, “Konstruktionen von Europa,” 18-21.

[22] van Middelaar, De passage naar Europa, 31.

[23] Eder, “A Theory of Collective Identity,” 435; Leerssen, “Eurotypes after Eurocentrism,” 86; Joep Leerssen, “The Camp and the Home: Europe as Myth and Metaphor,” National Stereotyping, Identity Politics, European Crises (2021): 126.

[24] Eder, “A Theory of Collective Identity,” 437; van Middelaar, De passage naar Europa, 31, 307.

[25] Gönül Bozoğlu, Mads Daugbjerg, Susannah Eckersley & Christopher Whitehead, Dimensions of Heritage and Memory: Multiple Europes and the Politics of Crisis (Routledge, 2019); Checkel & Katzenstein, “European identity”; Eder, “A Theory of Collective Identity,” 427-447; Leerssen, Spiegelpaleis Europa; Leerssen, “Stranger/Europe,” 7-25; Leerssen, “Eurotypes after Eurocentrism,” 85-98; Quenzel, “Konstruktionen von Europa”; Risse, A Community of Europeans; Shore, “Inventing the ‘People’s Europe’,” 779-800; Stråth, “A European Identity,” 387–401.

[26] Leerssen, Spiegelpaleis Europa, 189.

[27] Beck, Grande, and Cronin, Cosmopolitan Europe, 6; Mangiapane & Migliore, Images of Europe; Shore, “Inventing the ‘People’s Europe’,” 783; Stråth, “A European Identity,” 387–401.

[28] Eder, “A Theory of Collective Identity,” 442; Delanty, Inventing Europe, 1; Atalia Onițiu, “The Construction of European Identity in Fourth Grade History Handbooks,” Journal of Educational Sciences 40, no. 2 (2019): 44; Shore, “Inventing the ‘People’s Europe’,” 783; Stråth, “A European Identity,” 387–401.

[29] Bozoğlu, Daugbjerg, Eckersley & Whitehead, Dimensions of Heritage and Memory; Quincy Cloet, “Two Sides to Every Story(Teller): Competition, Continuity and Change in Narratives of European Integration,” Journal of Contemporary European Studies 25, no. 3 (2017): 291–306; Eder, “A Theory of Collective Identity,” European journal of social theory 12, no. 4 (2009): 442; Leerssen, Spiegelpaleis Europa; Leerssen, “Eurotypes after Eurocentrism,” 85-98; Quenzel, “Konstruktionen von Europa,” 95.

[30] Carpentier, “The European Assemblage,” 233; Eder, “A Theory of Collective Identity,” 441; Leerssen, Spiegelpaleis Europa; Leerssen, “Eurotypes after Eurocentrism,” 85-98.

[31] Delanty, Inventing Europe, 3; Leerssen, Spiegelpaleis Europa; Leerssen, “Stranger/Europe,” 7-25.

[32] Mangiapane & Migliore, Images of Europe ; Quenzel, “Konstruktionen von Europa,” 95.

[33] Bozoğlu, Daugbjerg, Eckersley & Whitehead, Dimensions of Heritage and Memory; Leerssen, “Eurotypes after Eurocentrism,” 88-89; Leerssen, “The Camp and the Home,” 127-128.

[34] Delanty, Inventing Europe, 3; Leerssen, “The Camp and the Home,” 127; Shore, “Inventing the ‘People’s Europe’,” 783.

[35] Leerssen, “Eurotypes after Eurocentrism,” 85-98.

[36] Quenzel, “Konstruktionen von Europa”

[37] Zeynep Arkan, “Defining ‘Europe’ and ‘Europeans’: Constructing Identity in the Education Policy of the European Union,” Federal Governance 10, no. 2 (2013): 37; David Coulby, “Post-Modernity, Education and European Identities,” Comparative Education 32, no. 2 (1996): 175-176; Quenzel, “Konstruktionen von Europa,”98-105.

[38] van Middelaar, De passage naar Europa, 31-38.

[39] Risse, A Community of Europeans.

[40] Risse, A Community of Europeans, 61.

[41] Leerssen, “Eurotypes after Eurocentrism,” 85-98.

[42] Monica Sassatelli, Becoming Europeans: Cultural Identity and Cultural Policies (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2009); Monica Sassatelli, “Europe’s Cosmopolitan Identity. Images of Unity in Diversity in the Euro,” Images of Europe (2021): 195–208.

[43] Shore, “In uno plures’(?),” 7, 12.

[44] Shore, “In uno plures’(?),”20.

[45] Delanty, Inventing Europe.

[46] van Middelaar, De passage naar Europa, 307.

[47] Risse, A Community of Europeans.

[48] Risse, A Community of Europeans, 50.

[49] Risse, A Community of Europeans, 61.

[50] Jürgen Habermas and Jacques Derrida, “February 15, or What Binds Europeans Together: A Plea for a Common Foreign Policy, Beginning in the Core of Europe,” Constellations 10, no. 3 (2003): 291–297.

[51] Beck, Grande, and Cronin, Cosmopolitan Europe; Habermas and Derrida, “February 15,” 291–297; Loobuyck, “Een gedeelde Europese identiteit,” 37-44.

[52] Shore, “In uno plures’(?),” 11.

[53] Wolfram Kaiser, “Limits of cultural engineering: actors and narratives in the European Parliament’s House of European History Project,” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 55, no. 3 (2017): 518; Kaiser and McMahon, “Narrating European Integration,” 151; Shore, “Inventing the ‘People’s Europe’,” 785.

[54] Shore, “In uno plures’(?),” 8.

[55] Eder, “A Theory of Collective Identity,” 434; Loobuyck, “Een gedeelde Europese identiteit,”37-44.

[56] Luis Bouza Garcia, “The ‘New Narrative Project’ and the Politicisation of the EU,” Journal of Contemporary European Studies 25, no. 3 (2017): 340–353; Eder, “A Theory of Collective Identity,” 434.

[57] Eder, “A Theory of Collective Identity,” 434.

[58] Declaration on European identity (Copenhagen, 14 December 1973) – CVCE; Onițiu, “The Construction of European Identity,” 43; Shore, “In uno plures’(?),” 13; Shore, “Inventing the ‘People’s Europe’,” 787-788; Stråth, “A European Identity,” 387–401.

[59] Loobuyck, “Een gedeelde Europese identiteit,” 37-44; Shore, “Inventing the ‘People’s Europe’,” 788-790; Shore, “In uno plures’(?),” 14-18.

[60] Arkan, “Defining ‘Europe’ and ‘Europeans’”; Quenzel, “Konstruktionen von Europa,”21; Shore, “Inventing the ‘People’s Europe’,” 779-790; Shore, “In uno plures’(?),” 7-26.

[61] Wolfram Kaiser, “Limits of cultural engineering: actors and narratives in the European Parliament’s House of European History Project,” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 55, no. 3 (2017): 518-534; Van Weyenberg, “‘Europe’ on Display”.

[62] Tuuli Lähdesmäki, Creating and governing cultural heritage in the European Union: the European heritage label (Verenigd Koninkrijk: Taylor & Francis, 2020).

[63] Antoinette Fage-Butler and Katja Gorbahn, “Europeanness in Aarhus 2017’s Programme of Events: Identity Constructions and Narratives,” Culture, Practice & Europeanization 5, no. 1 (2020): 16–33; Monica Sassatelli, “Imagined Europe,” European Journal of Social Theory 5, no. 4 (2002): 435–451.

[64] Quenzel, “Konstruktionen von Europa”; Shore, “Inventing the ‘People’s Europe’,” 779-800.

[65] Arkan, “Defining ‘Europe’ and ‘Europeans’,”35-46.

[66] Arkan, “Defining ‘Europe’ and ‘Europeans’,” 35-46.

[67] Risse, A Community of Europeans, 37; Sassatelli, Becoming Europeans.

[68] Fage-Butler and Gorbahn, “Europeanness in Aarhus 2017’s Programme of Events,” 16–33; Lähdesmäki, Creating and governing cultural heritage in the European Union; Monica Sassatelli, “Imagined Europe,” European Journal of Social Theory 5, no. 4 (2002): 435–451; Van Weyenberg, “‘Europe’ on Display”.

[69] Arkan, “Defining ‘Europe’ and ‘Europeans’”; Quenzel, “Konstruktionen von Europa”; Sassatelli, Becoming Europeans; Shore, “Inventing the ‘People’s Europe’,” 779-800.

[70] Leerssen, Spiegelpaleis Europa; Leerssen, “Stranger/Europe,” 7-25; Leerssen, “Eurotypes after Eurocentrism,” 85-98; Leerssen, “The Camp and the Home,” 125-141.

[71] Arkan, “Defining ‘Europe’ and ‘Europeans’,”35.

[72] Eder, “A Theory of Collective Identity,” 427-447; Leerssen, “Eurotypes after Eurocentrism,” 85-98.

[73] Eder, “A Theory of Collective Identity,” 427-447; van Middelaar, De passage naar Europa.

[74] Carpentier, “The European Assemblage,” 233; Eder, “A Theory of Collective Identity,” 441; Leerssen, Spiegelpaleis Europa; Leerssen, “Eurotypes after Eurocentrism,” 85-98.

[75] Arkan, “Defining ‘Europe’ and ‘Europeans’”.