The mechanical basis of evolutionary divergence in Darwin's finches

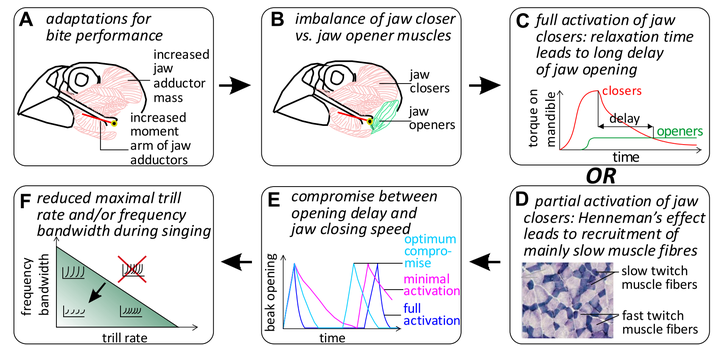

The beak of birds is used for several functions, e.g. feeding, drinking, fighting, preening, thermoregulation, singing, leading to a compromise between these diverse functions. Adaptive evolution in relation to the feeding ecology is an important driver for beak shape and size. In addition, for songbirds also the singing performance is an important driver, as females usually prefer more complex songs, with high trill rate and frequency. However, singing performance decreases in beaks adapted to high bite forces. This suggests a force-velocity trade-off in beak function. The biomechanical principles underlying this trade-off, are however still unclear. The aim of this study is to get a detailed and integrative understanding of how specialisation for increased bite force limits feeding and singing performance in finches. We want to better understand how morphology and muscle physiology of the cranial system limits performance, and how this constrained evolution in finches. Ten bird species from two families (Fringillidae and Estrildidae) are used to study morphology of the cranial system using CT scans and muscle fibre typing. Furthermore, their kinematics during feeding and singing are studied using video analysis and their muscle are studied for contractile properties. Finally, one species is used to analyse diet-induced phenotypic plasticity, by raising individuals with different kinds of seeds (hard- and soft-shelled seeds).

Collaborators

- Sam Van Wassenbergh (UA, PI)

- Dominique Adriaens (co-PI)

- Jana De Ridder (PhD student - UGent)

Keywords: evolution, kinematics, morphology, muscles, Fringillidae, Estrildidae, phenotypic plasticity, adaptive evolution, fibre typing, video analysis