Medieval latrine reveals ancient infection with African parasite in Bruges

(06-12-2024) In a surprising discovery, researchers have found evidence of an African intestinal parasite in a 500-year-old cesspit in Bruges. The find offers valuable insights into how diseases spread in the past.

The research, a collaboration between Canada's McMaster University and Ghent University, shows how migration and trade contributed to the spread of infectious diseases such as schistosomiasis. Today, this is still the second deadliest parasitic disease, after malaria, and is caused by Schistosoma parasites. These parasites can enter the body in water through the skin, travel to the intestines and lay eggs there.

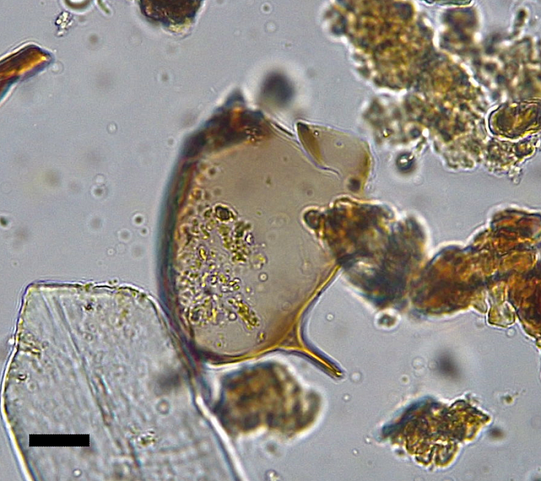

It is normally a disease mainly found in Africa. But Marissa Ledger, a researcher at McMaster University, discovered a preserved egg of Schistosoma mansoni in a 15th-century latrine in Bruges, thousands of kilometres away.

Hitchhiking with Mediterranean traders

The latrine was already discovered in 1996 during excavations in the Spanjaardstraat in Bruges, but its contents were only recently examined using new techniques within a research project at Ghent University (High tide, low tide). Among other things, the project researches foreign communities that lived and traded in medieval Bruges. Historical research by Mathijs Speecke (Ghent University) shows that the latrine belonged to, among others, Spanish traders, who were active in this part of the city mostly from the late fifteenth century onwards.

The parasite may have hitchhiked with these traders, who brought goods from Africa to Bruges. Bruges was an important hub for international trade at the time. Exotic products such as gold, ivory and spices found their way to the city via Spanish and other Mediterranean traders. The parasite probably came along unintentionally during one of those trade trips. On the other hand, a direct African presence cannot be completely ruled out. In fact, the first mention of an African person in Bruges dates back to 1440.

New insights thanks to organic material

The combination of rich historical sources and archaeological and parasitological data make this research quite unique. It helps to better understand human migration and disease transmission in the past. According to Maxime Poulain, archaeologist at Ghent University, the find attests to the complexity of medieval city life: ‘It not only gives a new insight into the daily lives of people in medieval Bruges, but also shows how the city - as an international hub for people, goods and ideas - inevitably provided for the spread of diseases.’

Koen Deforce, professor of archaeobotany at Ghent University, adds that the study of organic remains, such as the eggs of intestinal parasites, is becoming increasingly important in archaeology: ‘Whereas the focus used to be on studying objects made of clay and metal, we are now increasingly looking at organic material to learn more about the diet, health, hygiene and mobility of past populations.’

At McMaster University, Ledger now plans to proceed with analysing the parasite's genetics. By comparing these with modern variants, she hopes to gain more insight into how diseases are affected by migration over time.

Read more about the research Hoog tij, laag tij: het laatmiddeleeuwse havensysteem van Brugge als een maritiem-cultureel landschap.

Or read the scientific article at Cambridge University Press.

More info? Contact Maxime Poulain: maxime.poulain@ugent.be.